A Data- Driven Approach to Inclusive Education

Eva Gyarmathy[1]

Resumen: Este estudio examina el papel del perfil cognitivo en la promoción de una educación inclusiva, de acuerdo con el Pacto Mundial para la Educación del Papa Francisco. Mediante el Test de Perfil Cognitivo y Sensoriomotor, se evaluó a más de 1000 niños de entre 5 y 8 años con el fin de identificar las funciones cognitivas y sensoriomotoras fundamentales que predicen el éxito escolar. Los resultados ponen de relieve ocho áreas clave del desarrollo y muestran cómo la detección temprana permite intervenciones específicas. Los estudios de casos ilustran la eficacia de la prueba en diversos contextos educativos, demostrando cómo los datos pueden convertirse en un vector de equidad y compasión en la educación.

Palabras clave: perfil cognitivo, decisión basada en datos, enseñanza primaria, inclusión

Résumé : Cette étude examine le rôle du profilage cognitif dans la promotion d’une éducation inclusive, en accord avec le Pacte mondial pour l’éducation du pape François. À l’aide du Test de Profil Cognitif et Sensorimoteur, plus de 1 000 enfants âgés de 5 à 8 ans ont été évalués afin d’identifier les fonctions cognitives et sensorimotrices fondamentales prédictives de la réussite scolaire. Les résultats mettent en évidence huit domaines clés du développement et montrent comment la détection précoce permet des interventions ciblées. Des études de cas illustrent l’efficacité du test dans divers contextes éducatifs, démontrant comment les données peuvent devenir un vecteur d’équité et de compassion en éducation.

Mots-clés: profil cognitif, décision fondée sur les données, enseignement primaire, inclusion

Summary: This study investigates the role of cognitive profiling in promoting inclusive education, aligning with Pope Francis’s Global Compact on Education. Using the Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test, over 1,000 children aged 5 to 8 were assessed to identify foundational cognitive and sensorimotor functions predictive of academic success. The findings highlight eight key developmental domains and demonstrate how early detection enables targeted interventions. Case studies illustrate the test’s effectiveness across diverse educational contexts, showing how data can become a means of equity and compassion in education.

Keywords: cognitive profile, data-driven decision, primary education, inclusion

Introduction

The Meeting of Cold Technology and Hope

In today’s world, where education increasingly finds itself caught between social fault lines and rapid technological transformations, it has become urgent to rethink its purpose and tools. Technological developments promise innovation and inclusivity, yet digital solutions risk reducing learners to patterns and predictions, rather than empowering agents of hope.

The Catholic educational tradition has always understood hope through the lens of human dignity and communal responsibility. The Global Compact on Education aims to update this heritage, encouraging education to become a pathway toward solidarity, fraternity, and the common good.

The realm of education is seeing a growing adoption of data- driven approaches, promising personalized and more inclusive learning experiences. This study explores possible pathways and raises questions about the opportunities offered by data analytics and digital technologies. We seek directions that offer solutions not only for improving individual performance, but also for strengthening human relationships and communal life. Our proposition is that certain tools can genuinely contribute to reinforcing faith in the future and a shared sense of responsibility – both in individuals and in communities.

In this jubilee year, dedicated to the « Pilgrims of Hope, » it is especially timely to ask: how can the cold rationality of digital technologies be reconciled with the warm humanity of teaching? The aim of this study is to build a bridge between these two worlds, while uncovering the opportunities and dilemmas that lie within a reimagined pedagogy of inclusivity and hope.

Data-Driven Education

Data-driven education refers to the systematic use of data to inform and optimize teaching, learning, and educational decision- making. By leveraging data from various sources – such as student assessments, learning management systems, and behavioural analytics – a educators can tailor instruction, predict outcomes, and improve educational practices. The theoretical foundation of data-driven education is rooted in educational psychology, learning sciences, data science, and systems theory. This approach aligns with broader trends in evidence- based practice and the increasing availability of educational technologies.

Learning analytics is a core component of data-driven education, focusing on the measurement, collection, analysis, and reporting of data about learners and their contexts. Theoretical frameworks in this area include the Learning Analytics Model [0], which emphasizes the use of data to understand and optimize learning environments. The Educational Data Mining field [2] applies data mining techniques to educational datasets to uncover patterns and insights.

Data- driven education operates within complex educational ecosystems, where multiple stakeholders (students, teachers, administrators, policymakers) interact. Systems theory provides a framework for understanding these interactions. Educational systems take inputs (e.g., student data, resources), process them (e.g., teaching strategies, interventions), and produce outputs (e.g., learning outcomes, graduation rates). Data- driven approaches optimize each stage by identifying inefficiencies and improving resource allocation. Continuous data collection and analysis create feedback loops that enable iterative improvement.

Data- driven education aligns with the principles of evidence- based practice, which emphasizes the use of empirical evidence to guide decisions. Key concepts include:

1 Formative and Summative Assessment: Formative assessments provide ongoing data to inform instruction, while summative assessments evaluate learning outcomes. Data-driven systems integrate both types of assessments to create a comprehensive picture of student progress [3].

2 Predictive Analytics: By analysing historical data, predictive models can forecast student performance and identify potential challenges. This allows for proactive interventions, such as early warning systems for at- risk students [4].

3 Personalized Learning: Data-driven education enables the customization of learning experiences to meet individual needs, preferences, and goals. This is supported by theories such as Differentiated Instruction [5], which advocates for tailoring teaching methods to diverse learners.

While data- driven education offers significant benefits, it also raises important ethical and theoretical questions:

1 Privacy and Data Security: The collection and use of student data must comply with ethical standards and regulations, such as FERPA and GDPR. Theoretical frameworks like Privacy by Design emphasize the need to embed privacy protections into educational technologies [6].

2 Bias and Fairness: Data- driven systems can inadvertently perpetuate biases if not carefully designed. Theories of Algorithmic Fairness and Critical Data Studies highlight the importance of addressing bias in data collection, analysis, and interpretation [7].

3 Equity and Access: Data- driven education must ensure that all students, regardless of socioeconomic status, have access to the benefits of these technologies. Theories such as Digital Divide and Inclusive Education emphasize the need to address disparities in access and outcomes [8].

Data- driven education has transformative potential across various domains:

> Classroom instruction: Teachers can use data to differentiate instruction, monitor progress, and provide targeted support.

> Institutional decision- making: Schools and universities can use data to improve curriculum design, resource allocation, and policy development.

> Research and innovation: Large- scale datasets can be analysed to identify trends, test hypotheses, and develop new educational theories.

Cognitive Profile Tests

Cognitive profile testing refers to the systematic assessment of an individual’s cognitive abilities, including memory, attention, problem- solving, language, and executive functions. These tests are designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of an individual’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses, which can be applied in various fields such as education, clinical psychology, neuropsychology, and occupational settings. The theoretical foundation of cognitive profile testing is rooted in several key areas of psychological and neuroscientific research, including cognitive psychology, psychometrics, neuropsychology, and developmental psychology.

Cognitive profile testing is a multidisciplinary endeavour grounded in cognitive psychology, psychometrics, neuropsychology, and developmental psychology. By integrating theoretical insights and empirical research, these tests provide a robust framework for understanding and assessing human cognition. Cognitive profile testing has broad applications, including:

- Educational Planning: Tailoring learning strategies to students’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

- Occupational Settings: Assessing cognitive fit for specific roles or identifying training needs.

- Clinical Diagnosis: Identifying cognitive impairments associated with conditions such as dementia, traumatic brain injury, or ADHD.

- Research: Investigating cognitive processes and their neural correlates in different contexts.

Cognitive tests, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [9] and the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), are essentially cognitive profile tests because they provide a map of abilities. However, Wechsler tests lack sensorimotor function assessments, and the CANTAB subtests examined by Lenehan et al. [10] did not load on individual cognitive functions and may lack sensitivity in healthy populations. Neuropsychological assessments, such as the Halstead- Reitan Battery, are designed to detect cognitive impairments resulting from brain injuries or neurological disorders, providing insights into underlying neural mechanisms [11], but such tests are not designed to assess the background profile of everyday achievements.

Cognitive abilities evolve across the lifespan, requiring assessment tools that adapt to developmental changes. Childhood is marked by rapid growth in executive functions, memory, and language skills [12], while adulthood generally reflects stability in cognitive performance, with gradual declines in processing speed and working memory in later years [13]. Aging introduces further variability, with some individuals maintaining high levels of cognitive function despite the passage of time [14].

To ensure accurate measurement across different age groups, assessments such as the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children [15] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [16] have been developed. However, existing tools are often either lengthy and require specialized expertise, or overly brief and limited in informational value. This highlights the need for balanced instruments that are both accessible and comprehensive.

The Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test was designed with these key aspects in mind, emphasizing the relevant problem areas in its description and illustrating its practical applications through detailed case studies.

Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test

Introduction to the Test

The Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test evaluates the core functions and foundational skills essential for academic development. Its purpose is to deliver a comprehensive overview of individual or group strengths and areas needing improvement. This data serves as the basis for crafting targeted development plans and personalized teaching strategies that align with the specific needs of each group. Data- driven decision-making is especially crucial when supporting learners from low socio- cultural backgrounds or those with neurodevelopmental challenges.

The predecessor of the current test is the Hungarian adaptation of the International Cognitive Profile Test [17], a multilingual assessment tool designed to assess dyslexia in different languages [18][17]. An earlier online version of the Cognitive Profile Test has been used in several research studies [19][20][21].

The latest edition of the Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test is multilingual, available in English, German, Spanish, Finnish, Hungarian, and Ukrainian. This versatility allows for the assessment of multilingual children and supports its application in the assessment of immigrant children, or in cross-cultural research. The test items are intentionally designed to be engaging and competence-building, encouraging children’s active and enthusiastic participation. The test is accessible at no cost. The online version is user-friendly and can be administered by teachers without requiring specialized training (http://kognitivprofil.hu).

The development of the test has advanced to include a version specifically designed for young children. Leveraging modern technology, touch- screen devices now enable skill assessment through active child participation starting as early as age five. Sensorimotor tasks have been integrated alongside cognitive assessments, recognizing the importance of evaluating foundational sensorimotor functions that underpin cognitive development in early childhood. These tasks not only assess both domains in young children but are also applicable for adults, particularly in monitoring sensorimotor performance during cognitive decline in later life.

Description of the Test

The test is suitable for children and adults of different ages. The items on the test page are marked with letters (e.g., A, B, C) and colours (e.g., blue, yellow, green) to indicate which items are suitable for a particular age group. Age ranges are the following:

- A: 5–10 years old

- B: 7–13 years

- C: 10–16 years

- D: over 12 years

The large age overlap within the bands is necessary because children at very different stages of development may need to be tested. It is up to the investigator to decide which band to choose to measure a particular individual or group. The interpretation of the results will be valid within that band.

The test is uniquely structured to measure functions that can be reassessed annually, making it well- suited for both ongoing monitoring and impact evaluation. Results are reported using categorical classifications based on reference values, as well as detailed individual scores.

The categories are based on the data collected during the data collection period. We used the mean and standard deviation data for each task to create five categories:

- 5 – Excellent: Performance exceeds the mean by more than two standard deviations.

- 4 – Above Average: Performance is greater than one, but not more than two standard deviations above the mean.

- 3 – Average: Performance falls within one standard deviation above or below the mean.

- 2 – Needs Development: Performance is more than one, but less than two standard deviations below the mean.

- 1 – Requires Significant Development: Performance is more than two standard deviations below the mean.

Categories offer a quick summary of an individual’s strengths and weaknesses, while scores give detailed insights and are shown in radar charts. Downloadable data enables analysis for individuals, classes, or groups, and supports custom chart creation.

Benchmarks guide the developmental assessment of both individuals and groups using extensive data. Group profiles help interpret individual results, which should always be analysed within context to ensure effective, data- driven decisions.

The test assesses three main domains: cognitive functions, sensorimotor functions, and academic skills. Each area includes specific tasks:

- Cognitive functions: visual processing, executive functions

- Sensorimotor functions: movement rhythm, spatial orientation, visual and auditory perception, sequentiality

- Academic skills:

For older children/adults: words, numbers

For young children: numeracy, literacy, verbal functions, sensory- motor integration

Assessment outcomes not only inform individual learning plans but also support curriculum adjustments and targeted interventions at the group level. By mapping abilities across the assessed domains, educators and researchers can discern developmental patterns, strengths to be leveraged, and areas necessitating structured support. This comprehensive framework is designed to foster both immediate and long- term educational growth, ensuring that nuanced differences between learners are recognised and addressed with precision.

Crucially, such assessments move beyond surface-level performance, delving into the core processes underpinning learning and adaptation. Insights derived from these tools enable stakeholders to create environments where potential is maximised and barriers to achievement are systematically dismantled.

The test consists of twenty items and a neurodevelopmental questionnaire. The items are short; the whole test can be completed in one hour, but not all items have to be completed and not necessarily in one session. The nature of a profile test, and the fact that scores are given in categories as well as scores, allows the investigator to administer tasks appropriate to the purpose of the assessment, also considering the age of the subject. In this way, the testing time can be significantly reduced.

As the foundation of the assessment accommodates flexibility and efficiency, it also provides the granularity needed to discern which specific cognitive and sensorimotor factors most strongly correlate with educational attainment. By structuring collected data in a way that highlights individual profiles while permitting robust group comparisons, researchers can distil which elements of ability serve as reliable predictors for academic achievement.

This approach not only streamlines the evaluation process but also enhances the interpretative power of the results. Essential skills that underpin both learning and adaptation can thus be identified, with particular emphasis on those that, when absent or underdeveloped, significantly increase the risk of academic difficulties. The ability to tailor both the administration of the test and the analytic focus ensures that the assessment remains relevant across age groups and educational contexts, aligning with the overarching goal of fostering success for all learners.

Research

Goals

This research seeks to determine which sensorimotor and cognitive profiles are associated with academic achievement. Deficits in certain skills may affect school performance, but some skills and basic functions may have a significant impact. Identifying these factors is relevant for data-driven decision-making.

Here we present only the key indicators that most influence a child’s academic success.

Cognitive Functions

- Working memory: digit span backwards

- Auditory sequential memory: digit span

- Inhibitory control: go/no-go task

- Figural abstraction, abstract reasoning: logical matrices

- Visual processing speed: picture recognition from fragments

- Speech comprehension: understanding simple statements

Sensorimotor Functions

- Body scheme: body part identification

- Finger awareness: finger movement and recognition

- Spatial orientation: right/left differentiation

- Spatial relations: follow spatial instructions

- Spatial sequencing: arrange blocks by example

- Temporal sequencing: order story pictures

- Spatial memory: Corsi block test with animal images

- Balance: stand on one foot (eyes open/closed)

- Visuomotor speed: tap with each or both hands

- Speech sound discrimination: distinguishing similar words

- Musical sense: identify musical sounds

Academic Skills

- Math concepts: more-less-equal; basic operations

- Quantities processing speed: identify/comparisons

- Phonological awareness: first letter ID; spot real words

The Study Group and the Testing Situation

Our research project focuses on children aged 6 to 8, a developmentally pivotal stage that marks the beginning of formal schooling. From a psycho- neurological perspective, this period – often referred to as “middle childhood – is characterized by significant cognitive transformation, intertwined with shifts in motivational and social dynamics [22]. It represents a convergence point where previous developmental influences and emerging school-related experiences interact. This unique developmental window offers valuable opportunities for early intervention and support, provided that the environment is attuned to the children’s needs and can adapt the learning context accordingly.

The research was conducted across both state and church schools within the Diocese of Vác, Hungary, with 1,050 children aged 5 to 8 participating in the study and being monitored over a two- year period. Although individual socioeconomic backgrounds were not directly assessed, school- level statistical data were utilized to account for the proportion of disadvantaged and multiply disadvantaged children attending each institution.

The testing was carried out individually by the children’s teachers using tablets. The teachers familiarized themselves with the test beforehand so they could administer it confidently to the children. They reported that although they were initially apprehensive about the task, it ultimately turned out to be a pleasant experience for both the children and themselves as they were able to interact with their young students in a relaxed, engaging one- on- one setting.

Results

Profile Defining Academic Success

The successful development of individual school skills depends on the maturity of various sensorimotor and cognitive functions. We hypothesized that it is possible to identify the most essential of these – those that form the general foundation for learning at the beginning of formal education.

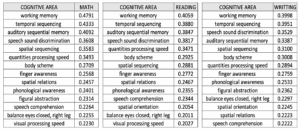

Study results clearly indicate that at least eight developmental domains play a decisive role in mastering school- related skills. The four most critical cognitive functions are working memory, temporal sequential processing, auditory sequential memory, and phonemic awareness.

Alongside these core indicators, additional developmental factors with a broader impact on learning also emerged through data analysis (see Table 1). Following the four main functions are spatial sequencing, number sense, body schema, and finger awareness.

Table 1. Correlations Between Early Sensorimotor-Cognitive Functions and Second-Grade Academic Skills

Further cognitive and sensorimotor functions that are crucial across all domains of academic competence include phonological awareness, the ability for figural abstraction, speech comprehension, spatial orientation and the perception of spatial relationships and balance, and finally visual processing speed.

Discussion of Results – Transforming the Learning Environment

The present study demonstrates that sensorimotor and cognitive foundations essential to the acquisition of academic skills can be reliably identified. Distinct developmental domains contributing to academic achievement—including those underpinning numeracy, literacy, and writing – share substantial overlap in their functional requirements. Thus, school readiness should not be conceptualized as domain-specific, but rather as an integrative developmental state encompassing a spectrum of interrelated capacities.

Historically, the segregation of mathematics, reading, and writing into discrete instructional units has reflected legacy practices rooted in traditional educational paradigms. However, this disciplinary compartmentalization has proven counterproductive to holistic child development. In the absence of robust diagnostic frameworks, educators have often relied on reductive, dichotomous categorizations – labelling students as either “good” or “poor” and “motivated” or “unmotivated” learners. Such binary assessments fail to capture the complexity of individual developmental trajectories and hinder the formulation of targeted interventions.

The introduction of developmental profiling and data- informed decision- making offers a transformative approach to educational planning. When detailed information is available regarding a child’s sensorimotor and cognitive readiness, educators are empowered to move beyond binary judgments toward constructing individualized developmental maps. These maps afford nuanced insight into learning potential and foster precision in pedagogical support strategies.

As long as core developmental capacities remain immature, instructional focus should prioritize the reinforcement of these foundational functions rather than premature academic skill training. This reconceptualization challenges the pedagogical utility of early subject- specific instruction and underscores the importance of developmental alignment in curriculum design.

Furthermore, children from socioculturally diverse backgrounds and those exhibiting neuroatypical developmental patterns frequently deviate from narrowly defined school- readiness criteria. The additional complexity introduced by immigration and multiculturalism places significant demands on educational systems. Inclusive pedagogy, therefore, necessitates the establishment of a baseline repertoire of competencies and adaptive behaviours that supports shared learning experiences across diverse student populations. In the absence of such common ground, educational disparities risk exacerbating existing social divides.

Settlement Size and Academic Achievement: A Nuanced Outlook

The relationship between the size of one’s settlement and academic achievement is intricate, shaped by a tapestry of influences – including socioeconomic status, cultural and ethnic background, access to educational resources, and the overall quality of schooling [23]. On a global scale, research has shown that students from smaller or rural communities often face academic hurdles compared to their peers in larger urban centres [24][25].

Children in urban regions – benefiting from diverse educational offerings, broader cultural exposure, and more varied family environments—tend to accumulate greater human capital than their rural counterparts [26]. The factors contributing to this gap may include limited access to high- quality teaching, scarce academic support services, and a lack of opportunity to engage with different cultural perspectives. Rural schools often grapple with retaining qualified educators and accessing the latest pedagogical tools, both of which impact student outcomes.

Our research groups comprise first-grade children who are just beginning their schooling journey, residing in communities of diverse sizes. The gender ratio among participants remains consistent. Based on the age distribution, 94.57% of the children in the study are between 6 and 7 years old, with only a small number falling outside this age range.

Table 2 Children Participating in Testing by Settlement Size

| Population of Settlements | Total Children N=870 |

| Under 3,000 inhabitants | Village N=232 |

| Between 3,000 and 30,000 inhabitants | Town N=275 |

| Over 30,000 inhabitants | City N=288 |

| Over 1 million inhabitants | Capital N=72 |

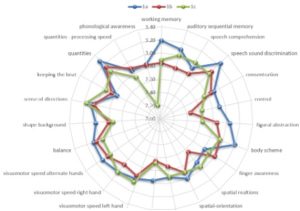

Our recent data analysis reveals that cognitive differences associated with living in rural areas are already detectable at the very start of first grade. While the deficits in cognitive functioning are present in almost every area assessed, they exert the strongest influence on those competencies that are essential for success in school, such as finger awareness, visuomotor abilities, sequential thinking, and working memory.

Figure 1. Differences in Cognitive Functioning Based on Settlement Size in School-Aged Children

Yet it’s essential to remember that cognitive potential is not determined solely by geography. Many children from smaller settlements thrive in creative, interpersonal, and practical domains. Moreover, these initial cognitive gaps are not fixed. These are areas where timely and targeted support may lead to significant changes. Early intervention, adaptive teaching strategies, and community- driven educational programs offer a promising path forward. With the right support, children from rural regions can not only catch up, but they can excel.

Every child holds the capacity to grow beyond the limits of their environment. Hope lives in the belief that where we start does not determine how far we can go. Data becomes our trusted ally when we interpret it not only with logic but with empathy – helping us uncover the hidden power within every child.

Case Studies

Village School Class in Trouble

In a small, remote village, a young teacher was close to giving up on the profession. Feeling inadequate and convinced she was failing her students, she began to question whether she could make a meaningful difference. Everything changed after reviewing the class’s test results.

The data revealed a deeper issue: the problem wasn’t the teacher’s skills, but the students’ developmental needs. Almost every child in the class faced serious challenges that made learning incredibly difficult without specialized support.

Key findings from the assessments included:

- All but two children displayed severely delayed working memory, making it nearly impossible to master reading or arithmetic.

- Seven students had significant difficulty distinguishing speech sounds, indicating weak phonological awareness – a fundamental skill for learning to read.

- Two children were at high risk for dyscalculia, struggling to connect numbers with quantities, which rendered arithmetic lessons ineffective.

- Most students were found to have learning disorders or intellectual delays, requiring intensive development and, in several cases, specialized education.

Interestingly, the only area of relative strength was body schema, while working memory and sequential processing were in critical need of support.

In response, the school district stepped in by assigning a special education teacher to work with the class. The teacher began weaving movement- based rhymes and developmental games into lessons, aiming to nurture the foundational skills essential for learning.

Through this tailored, multisensory approach, the classroom began to shift. The children engaged differently, and the young teacher – once burdened by doubt – found hope and purpose in a new kind of teaching. Progress was slow but real, unfolding with each playful rhyme and thoughtful game.

Cognitive Profiles and Developmental Patterns of Classes

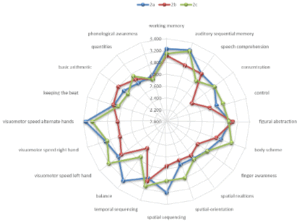

We present the possibilities of group assessment through the survey data of three first- grade classes in a large city school. After collectively downloading the test data of the children in each class, pie charts were created in Excel to visualize their cognitive profiles. These charts didn’t just reveal numbers – they told three very different stories about how children learn.

When evaluating student performance, level 3 is used as an average benchmark – a guidepost to understand how classes compare and to explore the unique cognitive profiles within each group. What emerges from the data is not uniformity, but a compelling story of difference, challenge, and potential.

The findings paint three distinct pictures:

- In Class 1.a, the indicators remain comfortably above 2.8, suggesting a broadly average level of development.

- Class 1.b reveals a noticeable lag in executive function, pointing to possible struggles with attention and impulse control – common markers of ADHD-type traits.

- In Class 1.c, the key concern lies in phonological awareness – a critical ability for decoding words and acquiring literacy.

Figure 3. Radar Graph Representation of the Performance Profiles of Three First-Grade Classes

But here is where the story shifts – from data to development. By second grade, progress had taken divergent paths. Class 1.b, (now 2.b) showed no measurable improvement, suggesting that no targeted intervention had yet reached them. Meanwhile, the children in Class 1.c, now 2.b began to turn a corner. In the second grade this class performed just as well on the phonological task as the other two classes. A thoughtful delay in introducing reading, paired with playful phonological games, sparked gradual growth. It was a reminder: when children are met where they are, remarkable things can happen.

On the other hand, while Class 2.b had experienced some challenges in control functioning during the previous year, recent observations suggest a slower pace in alternating hand tapping compared to their peers. This measure, often linked to higher-level cognitive functions like attention and working memory (Groot et al., 2022), may reflect a temporary developmental lag. Encouragingly, current test results do not indicate delays in those higher cognitive areas. What’s emerging is an opportunity: by recognizing the early signs of wider motor coordination difficulties, educators and specialists can now intervene more precisely and proactively. With timely support and focused strategies, the areas that once showed vulnerability have the potential to strengthen and realign—opening the door to renewed progress across domains.

Figure 4. Comparative Second-Grade Profiles of the Original Three Class Cohorts, Visualized on a Radar Plot

It’s important to note that class averages are only part of the picture. Behind every number lies a spectrum of individual development. Significant gaps within a class profile should not be ignored – they’re not just statistical anomalies but signals, asking educators to look closer.

Personalized instruction and attentive planning – especially in areas flagged as fragile – can unlock progress for both groups and individuals. Comparing each child’s results against their class can highlight who might benefit most from tailored support. And in every case, the goal remains the same: to foster a learning environment where every child can grow, at their own pace, with their own strengths. Hope, after all, isn’t just a feeling. It’s a strategy.

Bilingualism and Cognitive Profile Assessment

We illustrate the cognitive profile assessment procedure through the story of Rafael – a spirited, bilingual second- grader navigating an exceptional set of challenges.

Rafael is nine years old, with roots in two cultures: Hungarian through his mother and Spanish through his father. He completed first grade in a Spanish school, where nothing seemed out of the ordinary. But after his parents’ divorce, Rafael moved to Hungary with his mother and began second grade there. It was only then that learning difficulties – particularly in reading and spelling – started to surface.

Initially, his teacher assumed that bilingualism was behind the confusion. After all, juggling two languages can create temporary delays. But as the months passed and Rafael continued to mix up letters and struggle with reading, it became clear that something more might be happening.

To better understand the nature of Rafael’s difficulties, his teacher turned to the Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test. Rafael first completed the test in Hungarian, with results revealing a more complex picture:

- His overall cognitive abilities were notably strong.

- He had marked difficulties with working memory and temporal sequencing.

- His reading speed was inaccurate and slow.

- His arithmetic skills were solid.

- He was ambidextrous, with a slight preference for his right hand.

- He scored below average in spatial orientation tasks.

A month later, Rafael took the same test in Spanish. His performance followed a similar pattern—his reading in Spanish was even less developed than in Hungarian. Still, there were no issues in speech sound discrimination, and he showed intact letter- sound correspondence in both languages.

The conclusion: Rafael’s learning challenges stem not from bilingualism itself, but from weaknesses in spatial orientation, sequential processing, and working memory. Bilingualism amplified these difficulties, but it wasn’t the root cause. His ambidexterity may also contribute to spatial confusion – a common link between motor coordination and cognitive function.

What matters most now is not the diagnosis, but the path forward. Rafael’s profile shows promise, especially in math. But sequential processing affects not just literacy – it influences arithmetic as well. Without support, even his strongest skill could begin to slip. That’s why early intervention is so important. By strengthening spatial awareness and sequencing through targeted developmental exercises, Rafael has the chance to flourish – not despite his bilingual background, but alongside it.

Hope lies in understanding. With the right tools and tailored support, Rafael’s story can shift from struggle to strength, and from complexity to clarity.

Discussion

This study offers a compelling intersection between technology- driven assessment and the humanistic goals of inclusive education, particularly within Catholic pedagogical contexts. By operationalizing the principles of Pope Francis’s Global Compact on Education, it reframes hope not as abstract optimism but as an actionable strategy rooted in cognitive science and developmental psychology.

The Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test proved highly effective in identifying critical developmental domains linked to academic success. The strong predictive power of working memory, sequential processing, phonemic awareness, and sensorimotor integration underscores the importance of shifting educational diagnostics from surface- level performance toward foundational functions. This is especially relevant for children in the early stages of schooling (ages 5–8), where intervention timing can influence long- term trajectories.

The utility of the test was further validated through diverse case studies – spanning rural classrooms, neurodivergent learners, and bilingual students – which reveal the test’s adaptability across contexts. These narratives emphasize how data- informed decision- making can transform educational planning, not only by pinpointing developmental delays, but also by nurturing teacher agency and supporting individualized growth.

Importantly, the study critiques traditional subject-based instruction models, advocating instead for developmental alignment. The findings support a paradigm in which instruction builds upon sensorimotor and cognitive readiness rather than prematurely demanding academic output. Such a model empowers educators to design curricula responsive to individual profiles rather than standardized norms.

The results also shed light on systemic inequities, such as settlement size and resource availability, that shape cognitive readiness. Children from smaller or underserved regions displayed developmental gaps in key areas – gaps that are not static but open to targeted intervention. This reinforces the ethical imperative of educational equity and personalized support.

In sum, the integration of cognitive profiling into educational offers more than diagnostic value: it cultivates environments where each learner’s unique pathway is acknowledged and supported. Data, interpreted with empathy and purpose, becomes a tool for transformation – reconciling technological precision with the spiritual and developmental needs of children, and anchoring hope within a framework of evidence-based care.

Conclusion

This study affirms the transformative power of data- driven decision making and cognitive profiling as developmental tools in education. By identifying foundational functions – such as working memory, sequential processing, and sensorimotor skills – that strongly predict academic success, educators gain precise insights that enable individualized support. The Sensorimotor and Cognitive Profile Test not only reveals hidden challenges but also elevates teacher agency, bringing renewed purpose to pedagogical practice.

Importantly, the research reframes the use of technology within education – not as a detached mechanism of evaluation, but as an empathetic tool for nurturing potential and fostering equity. When combined with contextual understanding and compassionate teaching, data becomes a bridge between cold analytics and warm humanity.

Within Catholic educational frameworks, cognitive profiling aligns seamlessly with the mission of empowering each learner as a dignified individual. Hope, in this sense, is no longer just a virtue – it is made visible through actionable insights, inclusive strategies, and the belief that every child holds promise waiting to be realized.

________________________________

References

| [1] | Siemens, G., Learning analytics: The emergence of a discipline, American Behavioral Scientist, 2013, 57(10), pp. 1380–1400. |

| [2] | Baker, R. S., & Yacef, K., The state of educational data mining in 2009: A review and future visions, Journal of Educational Data Mining, 2009, 1(1), pp. 3–17. |

| [3] | Ismail, S. M., Rahul, D. R., Patra, I., & Rezvani, E., Formative vs. summative assessment: impacts on academic motivation, attitude toward learning, test anxiety, and self- regulation skill, Language Testing in Asia, 2022, 12(1), Article 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468- 022- 00191- 4 |

| [4] | Wach, M., & Chomiak- Orsa, I., The application of predictive analysis in decision- making processes on the example of mining company’s investment projects, Procedia Computer Science, 2021, 192, pp. 5058–5066. |

| [5] | Tomlinson, C. A., Differentiated instruction, in Fundamentals of Gifted Education, New York, Routledge, 2017, pp. 279–292. |

| [6] | Romanou, A., The necessity of the implementation of Privacy by Design in sectors where data protection concerns arise, Computer Law & Security Review, 2017, 34(1), pp. 99–110. |

| [7] | Starke, C., Baleis, J., Keller, B., & Marcinkowski, F., Fairness perceptions of algorithmic decision- making: A systematic review of the empirical literature, Big Data & Society, 2022, 9(2), Article 20539517221115189. |

| [8] | Lythreatis, S., Singh, S. K., & El- Kassar, A. N., The digital divide: A review and future research agenda, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2022, 175, Article 121359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121359 |

| [9] | Wechsler, D., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition (WAIS- IV), APA PsycTests [database record], 2008. https://doi.org/10.1037/t15169- 000 |

| [10] | Lenehan, M. E., Summers, M. J., Saunders, N. L., Summers, J. J., & Vickers, J. C., Does the Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) Distinguish Between Cognitive Domains in Healthy Older Adults?, Assessment, 2016, 23(2), pp. 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115581474 |

| [11] | Rohling, M. L., Williamson, D. J., Miller, L. S., & Adams, R. L., Using the Halstead- Reitan Battery to diagnose brain damage: a comparison of the predictive power of traditional techniques to Rohling’s Interpretive Method, The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 2003, 17(4), pp. 531–543. https://doi.org/10.1076/clin.17.4.531.27938 |

| [12] | Diamond, A., Executive functions, Annual Review of Psychology, 2013, 64(1), pp. 135–168. |

| [13] | Salthouse, T. A., When does age- related cognitive decline begin?, Neurobiology of Aging, 2009, 30(4), pp. 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023 |

| [14] | Park, D. C., & Reuter- Lorenz, P., The adaptive brain: aging and neurocognitive scaffolding, Annual Review of Psychology, 2009, 60, pp. 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093656 |

| [15] | Lichtenberger, E. O., Sotelo- Dynega, M., & Kaufman, A. S., The Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children—Second Edition, in Naglieri, J. A., & Goldstein, S. (Eds.), Practitioner’s Guide to Assessing Intelligence and Achievement, Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009, pp. 61–93. |

| [16] | Nasreddine, Z. S., et al., The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2005, 53(4), pp. 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532- 5415.2005.53221.x |

| [17] | Smythe, I., Cognitive factors underlying reading and spelling difficulties: a cross- linguistic study, PhD thesis, University of Surrey, 2002. |

| [18] | Gyarmathy É., Smythe, I., Többnyelvűség és az olvasási zavarok, Erdélyi Pszichológiai Szemle, 2000, December, pp. 63–76. |

| [19] | Kertzman, S., et al., Web- based Real- time Neuropsychological Assessment in Dyslexia, BMC Psychiatry, 2017, BPSY- D- 16. ISSN 1471- 244X. |

| [20] | Gyarmathy É., Gyarmathy Zs., Szabó Z., Pap A., & Kraiciné Szokoly M., Tizenévesek és felnőttek kognitív profiljának online mérése, Opus et Educatio, 2019, 6(3), pp. 297–309. http://opuseteducatio.hu/index.php/opusHU/article/view/330/574 |

| [21] | Gyarmathy É., Gyarmathy Zs., Szabó Z., A Sakkpalota képességfejlesztő program hatásvizsgálata, Új Pedagógiai Szemle, 2021, 71(03–04). |

| [22] | Del Giudice, M., Middle childhood: An evolutionary‐developmental synthesis, Child Development Perspectives, 2014, 8(4), pp. 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12084 |

| [23] | Miller, L. C., et al., Settlement size and academic achievement: A nuanced outlook, 2019. |

| [24] | Sullivan, A., et al., Rural education and achievement gaps, 2018. |

| [25] | Sumi, C., et al., Educational disparities in rural communities, 2021. |

| [26] | van Maarseveen, M., Urban- rural differences in human capital accumulation, 2021. |

| [27] | Groot, J. M., et al., Catching wandering minds with tapping fingers: neural and behavioral insights into task- unrelated cognition, Cerebral Cortex, 2022, 32(20), pp. 4447–4463. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab494 |

__________________________________

Pour citer cet article

Référence électronique : Eva Gyarmathy « Empowering Hope through Cognitive Profiling: A Data- Driven Approach to Inclusive Education », Educatio [En ligne], 16 bis | 2026. URL : https://revue-educatio.eu

Droits d’auteurs

Tous droits réservés

[1] Apor Vilmos Catholic College, Hungary